Local power in the age of digital policing

Last October the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) gave ride-alongs to reporters, showing off their effort to crack down on “scooter gangs.” In a trend started in L.A. by the Santa Monica-based startup, Bird, shiny new electric scooters were appearing by the tens of thousands on city streets around the globe, available for rent by the minute via smartphone apps. The devices were operated by familiar names in digital mobility like Uber and Lyft, along with an almost exponentially growing number of tiny companies. For the last few years, seemingly anyone with access to venture capital was attempting to deploy some new form-factor of electrified app-mediated mobility. As they proliferated they turned the transport world on its head, and resurfaced longstanding questions about the relationship between transport policy, policing, and public space.

A clip from a 2019 video of a late-night group scooter ride in L.A., ending in a chase by police helicopters and arrests.

My first attempt riding an electric scooter was in 2018 in a subterranean parking garage of a suburban DC mall. I found a fully charged Lime scooter hiding two levels below ground and thought the spiraling ramps would be a fun place to try one out. While I was fiddling with the app on my phone, a garage employee noticed what I was doing and came running towards me yelling that the scooter “belonged to the garage” and was not available to rent. The Lime app disagreed about the ownership status, but regardless, he had a reason to try to stop me: the scooter was his ride home after a late-night shift in place inaccessible to anyone without a car.

Today, folks with and without cars, along with tourists and more than a few drunken midnight revelers use these devices to zip down city streets, and sometimes interstate highways, reclaiming space long considered the domain of cars. But the scooters also anger many residents and as unused devices pile up on sidewalks they create a host of new logistical challenges for already overtaxed city transport officials.

But by last October, things had reached a new level with television news stories describing helicopter chases as the LAPD hunted down and arrested groups of teens criss-crossing the city on both rented and personally owned scooters. One story highlighted the LAPD’s new found superpower for combatting unruly riders: disabling scooters via remote control. The police called companies that operated the rental scooters and had them shut off mid-ride, a practice apparently implemented without considering due process or the safety risk of unexpectedly disabling a vehicle while in motion. One online forum run by AR-15 gun owners commented on the news videos with racially charged statements about the riders. But even that group thought the LAPD response was too much. As one commenter wrote, “Looks like a lot of harmless fun being had. Really L.A.P.D.? A chopper?”

LAPD officer arresting a scooter rider.

Over the last few years the “Scooter Wars,” a label applied by industry insiders to this moment of technological, regulatory, and cultural conflict, has become a proxy fight in a much larger battle for the future of the city. The debate over scooters represents a shift in both how new private sector business models interface with public space, and how new digital surveillance and enforcement technologies are changing the way we police streets. As LAPD’s reporter ride-alongs— complete with remote control traffic stops— show us, you don’t have to be a legal scholar to see the significance of what’s happening.

I've been involved in building public digital infrastructure for over a decade. What I've witnessed over the last two years has forced me reconsider much of what I believe (and thought I knew) about urban policy and technology. What follows is the beginning of documenting the discussions I've had and what I've learned. Much of this essay focuses on questions that began in L.A. but it is about a bigger conversation that’s unfolding in communities around the world. I share this in the hope that it contributes to the broader effort underway to reform the institutions that govern our cities.

Policing streets

The arrival of “dockless scooters” is not the first time the LAPD and city residents have clashed as a new form of mobility changed the makeup of public streets. As Cal State professor Denise Sandoval writes in The Politics of Low and Slow, the “lowrider,” a cultural phenomenon and mode of transportation claimed by both Black and Chicano communities in post-war Los Angeles, was also an act of technologically-enabled rebellion. “Because the California vehicle code stipulated that no part of the car could be lower than the bottom portion of the wheel rim, the police often wrote tickets to owners of lowriders.” Complex hydraulic lift systems allowed some drivers to switch to a street-legal height when the police were near, but lowrider drivers still felt they were targeted more frequently in traffic stops than the arguably more dangerous (and whiter) hot-rodders also common on L.A. streets.

The term “lowrider” itself was purportedly coined by the LAPD following the Watts Uprising in 1965. Those six days of unrest led to the death of thirty-four people in the Watts neighborhood of L.A., and were caused in part by a long-standing pattern of police violence against Black residents that boiled over following a violent traffic stop. While the police used “lowrider” as a “derogatory term for the young black kids that were causing all the trouble,” referencing a quote from another author, Sandoval writes, “youth and young adults redefined it as a source of cultural pride.” The 2005 documentary Sunday Driver explores how forty years later, lowrider culture, and related car clubs remain a source of pride, innovation, and artistry in Los Angeles, and a continued target for the police.

In one of the news stories about the scooter chases last fall, an LAPD officer cited a link between the scooter riders and a modern faction of the lowrider clubs as a part of the justification for police action.

A scooter parked in a suburban mall garage.

Many who work on transport policy are quick to point out they are not the police. However, this argument fails to recognize the longstanding role that transport policy, and transport policy makers, have played in co-creating laws that police enforce—laws we know cause direct and disproportionate harm. Tragically, those laws and the built environment we’ve constructed as planners and policymakers pursuing a more orderly, efficient, and “safer” city are at the heart of the profound racial injustice being protested against in cities all across the country today.

Contemporary urbanists, people interested in building streets that welcome walkers and cyclists not just move cars, often reference how the birth of the automobile ushered in policing of pedestrians, and the demonization of “jaywalkers.”

But the urbanist community talks much less frequently about how transport policy gave rise to modern policing itself. In her groundbreaking book, Policing the Open Road, historian and law professor Sarah Seo details how cars and, more specifically, the “traffic stop” transformed US criminal procedure and undermined fundamental constitutional rights. Seo writes, “the revolution in automotive freedom coincided with an equally unprecedented expansion in the police’s discretionary power.” Ultimately, “the multitude of traffic laws everyone disregarded at one time or another gave the police what amounted to a general warrant to stop anyone.” And as is all too obvious now, that discretionary power in policing streets is not applied equally—the fraught reality of “automotive freedom” is deeply linked with racial discrimination and police violence.

Transport policy is a powerful tool for encoding injustice. We use seemingly benign traffic regulations and design choices to govern peoples’ access to public space in ways that define the racial and economic hierarchy of the American city. Yet the transport policy practitioner community—traditionally white, often economically advantaged and, until recently, almost always male—rarely reflects or includes the communities its work impacts. As communities across the country reconsider how they’re policed it is crucial that we also consider where many of those forms of policing began and work toward a more comprehensive reform of transport policy and the ways we govern public infrastructure in pursuit of more equitable and just communities.

Building the digital traffic cop

Unfortunately, it’s increasingly clear that instead of making streets safer for all, many cities around the world following Los Angeles’ lead, deploying new digital infrastructure that expands on the transport and urban policy community’s longstanding tradition of building cities through surveillance, policing, and exclusion.

For more than a year before the LAPD helicopter chase stories aired, the L.A. Department of Transportation (LADOT) pushed to create its own system to track and control vehicles in real-time using a technology called “active management,” built into its newly conceived “Mobility Data Specification” (MDS).

During the summer of 2018, just a few weeks after attempting to ride the scooter in a mall parking garage, I was asked by LADOT to collaborate with them on the development of MDS. As the co-founder of a nonprofit researching new forms of digital urban infrastructure I found the project compelling: a city leading the development of data standards ostensibly for managing city-permitted mobility services.

But early in our conversations it became clear the city’s plans went far beyond regulatory challenges related to scooters, or other private, city-permitted services. Officials pointed to the public safety concerns and nuisance caused by scooters as justification to collect extraordinarily detailed real-time location data from scooters while parked and in-use. Ultimately they sought to intervene in trips, requiring specific routes or restricting use in certain areas, even dynamically changing rules to alter riders’ behavior while in motion—a similar but substantially more expansive version of the LAPD’s remote control traffic stops.

Once perfected, LADOT hoped to apply this data and regulatory infrastructure to many other forms of digitally-mediated transport, using scooters as a testbed. As one of the private sector architects of this system said at a LADOT-sponsored event, while standing in front of a slide presentation containing images from the Jetsons, “Scooters are just like autonomous vehicles, they’re controlled by mobile phones.” During the same event LADOT Director Seleta Reynolds said their goal for MDS was to create a “single digital truth,” a system for real-time monitoring and control of all urban transportation.

I also spoke at this event about my organization’s work to map streets and reduce the surveillance risks associated with analyzing citizen-generated location data for transport planning. When I was asked a question by an audience member about privacy concerns related to data collected by MDS, one of the event organizers interjected, answering that because the GPS data from citizens “didn’t contain things like people’s names” privacy concerns didn’t apply. This is a point of view at odds with both contemporary privacy research and law, which recognizes the ease with which so-called “anonymous” data can be re-identified.

Shortly after this event, in the winter of 2019, I withdrew my support for LADOT’s work. Witnessing efforts to expand their vision for surveillance and control to other cities I wrote an email to Reynolds citing concerns about citizen privacy, the opaque role of the city’s private sector partners, and the unjustifiably expansive form of control the city imagined:

I’m concerned with LADOT’s continued focus on “active” real-time management of citizen movement as part of [MDS]. The city has a clear right and responsibility to actively manage streets, but does not have a right to directly manage the movement of people through intervention in individual trips.

I don’t know of a single street management goal that requires knowledge of (or direct interaction with) a specific traveler while in motion in order to achieve success. I also don’t understand the legal authority a city has to tell a specific traveler they can or can’t use a street for a specific trip. LADOT’s stated approach raises significant civil liberties questions around what rights individuals have to public space and on what basis limitations on individual trips are made.

Reynolds responded:

It’s about all parties having better communications and effective interaction between government and businesses operating for-profit scooters on public streets. The intent is not and will not be surveillance or direct citizen movement intervention (beyond usual safety measures of traffic signals, identifying street closures, etc).

One area I continue to wrestle with is the following: if the city takes a passive approach - publishing our muni code and restrictions for example very much the way we do today even if they are done more elegantly or in a more easily-digestible format, then my enforcement and regulatory role continues to be a time and labor-intensive process, almost impossible at scale. I have applications for over 35,000 scooters in a city with 7,500 miles of streets. I am enforcing a set of regulations set by council - some of which want their entire districts exempt from the program, others of which want to exclude them from individual blocks. Others of whom change their minds regularly. Further, my impression is that a passive approach does not change the way in which the city manages its public realm or holds businesses accountable other than in a very piecemeal way that relies on data from the operators themselves. That brand of fox watching the henhouse has not proved effective up until now.

Simply put, it’s too costly to chase everyone with a helicopter.

But who needs a helicopter if the city can control and preemptively exclude people from neighborhoods where they aren’t welcome?

Reynolds’ reference to the demands of city council members and their desire to cordon off sections of the city or even specific blocks is key part of this story—that same city council pressure almost certainly played a role in the LAPD scooter chases. The goal was not to improve safety or hold companies accountable for operational performance, but to create new digital enforcement tools that allow residents to ban others from using the scooters in their neighborhoods.

But more importantly, Reyonolds’ intention to a shift from “passive” management of streets to “active” management of people using streets, describes an entirely new model of enforcement and a fundamentally different way of thinking about citizens’ right to public space. Public streets are, after all, public.

The type of “active management” Reynolds describes is, at its core, discriminatory. While cities can and should create tools for digitally managing public space and the private platforms, like Uber and Amazon, using that space, those regulatory tools should not regulate an individual's movement. These types of rules are an expansion of discretionary policing, and are at odds with both California law and more fundamental constitutional rights.

In my numerous meetings with LADOT staff and the private sector architects of their digital tracking and enforcement system, they repeatedly made clear that they were actually uninterested in regulating scooters but found them useful politically as a first step towards a broader transformation of the governance of public space. The public backlash against scooters, their riders, and the many legitimate management challenges cities faced as these fleets deployed opened the door on a new way of policing streets via real-time tracking and intervention in citizens’ movement. Once these technologies were developed, and the legal framework for their use established, they could be applied elsewhere. Surveillant digital infrastructure like L.A. proposed could allow cities around the world to expand the scope of laws governing streets while reducing the burden of enforcement, tracking and directly intervening in trips while in motion.

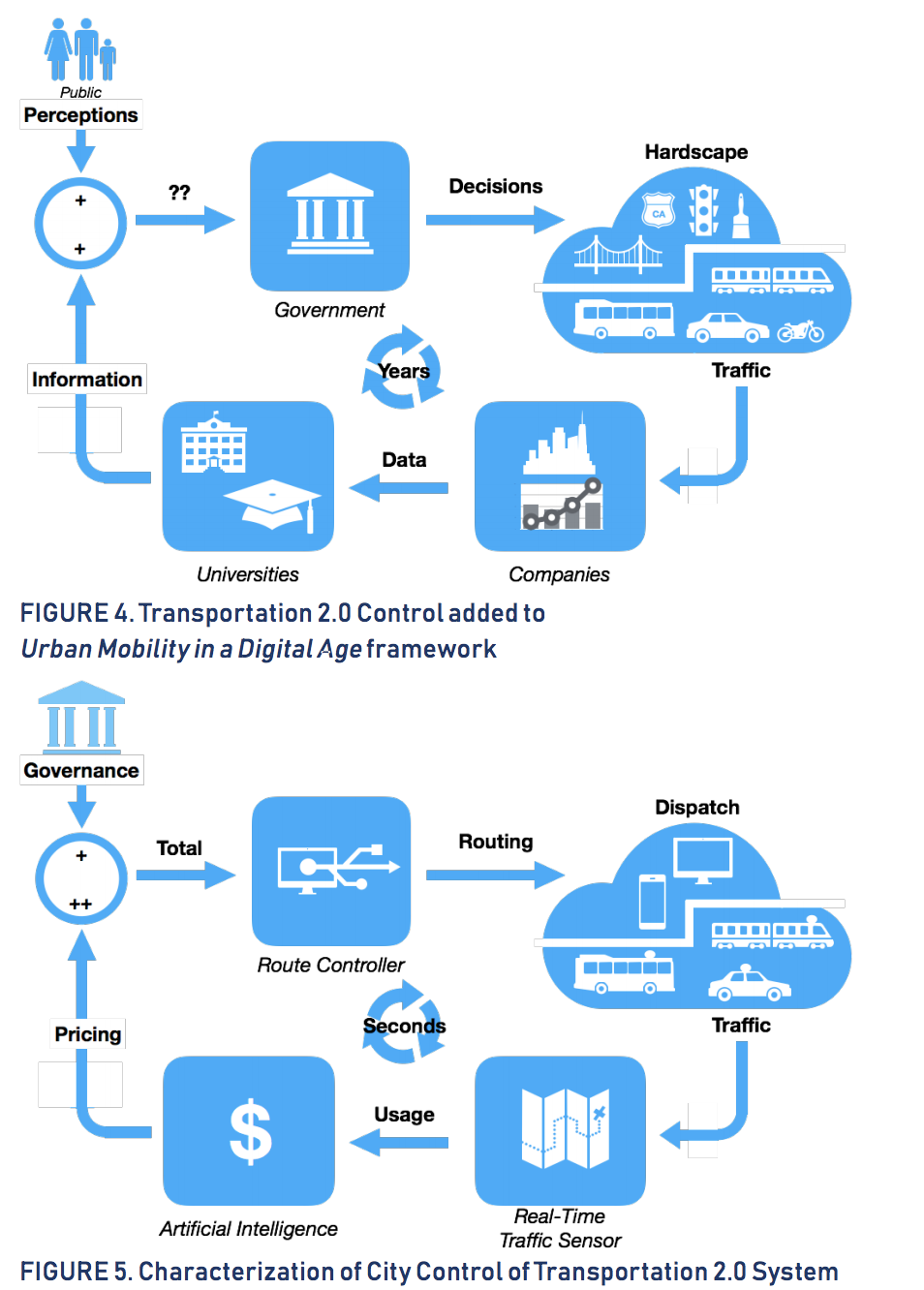

Despite the already problematic lack of representation by those directly impacted by its transport policies, LADOT 2018 Strategic Implementation Plan signaled a shift towards an even more technocratic approach to policy making. One diagram in the report depicts how cities could replace more traditional infrastructure planning processes with direct, real-time routing and control of people in motion. Putting aside questions of technical feasibility, this approach confuses transport “planning” with traffic enforcement. And LADOT’s vision for route-based control extends beyond existing forms of enforcement, which under California law cannot limit where vehicles travel. Active management, as LADOT frames it, defines transport policy as an algorithmic optimization challenge, and fails to recognize the inherently political (and discriminatory) nature of restricting use of public space.

A diagram of LADOT's proposed "Transportation 2.0" city control system from their 2018 Strategic Implementation Plan. According to the diagram, this shift replaces the current combination of “public perceptions” and expert-filtered “information” with an “artificial intelligence” augmented “governance” process. Appropriately, the cover page of this report features a quote from William Gibson.

Later in 2019 we started to see how LADOT's interest in routing, and its desire to digitally exclude travelers from specific neighborhoods, was not limited to scooters and the “foxes” operating private mobility services.

In an unprecedented move outlined in an LADOT memo to city council, LADOT staff requested that companies, including Apple and Google, alter the routing algorithms used in their maps to limit car trips through some of the cities’ wealthiest neighborhoods. The specifics of the conversations with the companies have never been disclosed, but according to the memo, at least some of the companies complied in some way as part of a pilot program to reduce travel through L.A.’s Sherman Oaks neighborhood.

On the surface this type of intervention seems reasonable, these routing algorithms do shift longstanding traffic patterns, putting more cars on streets that have previously been bypassed. However the legal reality and history of regulating “through traffic” is more complex.

In a 1960 Missouri Law Review article, Public Power to Close Residential Streets to Through Traffic, law and planning professor William Weismantel explores the limits of restricting access to public streets. St. Louis has been in the vanguard of exclusionary urban policy since the late 1860s, when wealthy landowners built the US’ first gated inner city neighborhoods known as “private places.” Despite that history, even in Missouri the ability to restrict use of public streets is much more limited than what LADOT proposed. Weismantel's article noted after a “street has been dedicated to public use the public cannot be completely excluded, nor may the use of such a street be limited only of those living in the subdivision.” Instead, he argues that cities should use their power to close streets at one end, or place barriers mid-block to physically prevent through traffic (a design practice that not only limits through traffic, but slows cars driven by neighbors—improving both street safety and reducing traffic volume).

LADOT initially proposed exactly this type of physical design intervention but the Sherman Oaks community rejected the changes citing inconvenience to neighborhood residents. In his article Weismantel noted that cities have the legal right to make this type of design change and that “land owners cannot complain about indirection or extra distance as a result of such action, provided some access to the street system remains open to them.” Regardless, LADOT acquiesced to neighborhood demands, kept the streets open, and instead pursued a strategy of digitally closing off Sherman Oaks to cars without destinations in the neighborhood.

The kind of traffic control Weismantel argued for in 1960 is increasingly common today as part of a renaissance in pedestrian- and cyclist-friendly urban design. But despite its virtues, physically redesigning streets also has a long and problematic history as a tool for encoding discrimination. The City of Memphis did exactly this in 1970, closing streets that connected predominately white and Black neighborhoods. In a deeply flawed and contentious decision the Supreme Court ultimately upheld the design change, ignoring its explicitly discriminatory animus.

Even then, implementing traffic restrictions via physical changes offers significant advantages over digital enforcement that discriminates based on who's using the street.

First, physical alterations are more explicit and transparent: physical changes to the street are in plain sight and, unlike an algorithmic tweak in routing engines, anyone can understand and debate the impact. If not for a memo to city council becoming public, no one would even know the algorithmic change to Sherman Oaks maps was made, and today we still don't know what was proposed or implemented.

Second, anyone using the street is impacted in the same way regardless of who they are. Obviously some designs exacerbate existing divisions and inequality, like Memphis intentionally placing barriers between white neighborhoods and predominately Black neighborhoods. But even despite the possibility of intentionally exclusionary design, streets altered by physical design changes still remain a public space. This leads to the third, and perhaps most important benefit: physical design changes do not depend on policing or surveillant forms of enforcement to achieve impact.

California cities have made previous attempts to limit who can use public streets, similar to what LADOT has attempted in Sherman Oaks, only to have these rules struck down in state courts. For example, in the 1979 lawsuit City of Lafayette v. County of Contra Costa, Lafayette officials argued that the city had the power to close Happy Valley Road, a local public street and important thoroughfare, to non-resident through traffic. The courts found “the City [is] without police power, or other authority, to deny use of Happy Valley Road to some members of the traveling public, while granting it to others.” In explaining its rationale the court cited previous cases related to the government's ability to deny an individual's right to travel on public roads:

Fundamentally it must be recognized that in this country 'Highways are for the use of the traveling public, and all have ... the right to use them in a reasonable and proper manner, and subject to proper regulations as to the manner of use.' ... 'The streets of a city belong to the people of the state, and the use thereof is an inalienable right of every citizen, subject to legislative control or such reasonable regulations as to the traffic thereon or the manner of using them as the legislature may deem wise or proper to adopt and impose.' ... 'Streets and highways are established and maintained primarily for purposes of travel and transportation by the public, and uses incidental thereto. Such travel may be for either business or pleasure ... The use of highways for purposes of travel and transportation is not a mere privilege, but a common and fundamental right, of which the public and individuals cannot rightfully be deprived ... [A]ll persons have an equal right to use them for purposes of travel by proper means, and with due regard for the corresponding rights of others'.

Today, California cities do have the power to limit “through traffic” temporarily, thanks to a law, AB 1334 passed in 1992, designed to aid police targeting drug and gang activity. The bill was sponsored by an L.A. metro-area legislator at the same moment the city was reeling from the beating of Rodney King by LAPD. That law expanded local police power, providing a new justification for discretionary traffic stops. Anyone who appeared to be from outside the neighborhood could now be legally pulled over by police and questioned. (These laws originally designed to expand police powers are what enabled the recent “local traffic only” closures piloted by many California cities in response to the COVID pandemic.)

The explicitly exclusionary intent of these regulations and their deeply problematic implementation via discretionary policing isn’t their only harm. These interventions also fail to recognize the zero-sum nature of routing: a car trip that doesn’t go through Sherman Oaks will still happen, it will just end up in someone else’s neighborhood—perhaps one without the political clout necessary to alter maps. And because Sherman Oaks residents also fought to stop a major transit project in the nearby Sepulveda Pass, claiming it would “destroy [the] community’s light, air, and privacy,” drivers coming through their neighborhood have no actual alternatives.

The expansion of city power via digital enforcement that LADOT proposes differs substantially from what old-fashioned, physical laws actually allow. In this case of Sherman Oaks, L.A.’s new “digital truth” is at odds with the laws that govern its streets. One mapping company employee familiar with the project called it “disinformation.”

It turns out LADOT’s new found power of truth isn't actually new—it's an already familiar and anti-urban form of power that has more to do with policing public space than managing new technology. These new enforcement systems digitally encode a longstanding desire to partition cities. And they work just like the tools transportation and urban policymakers have long used to physically segregate communities along racial and economic lines.

The displacement, or cordoning off of entire city neighborhoods based on race was an explicit goal in building the national highway system—transport policymakers used eminent domain and bulldozers to punch through and push aside Black neighborhoods in cities across the country. Land use policy and regulation has always been a tool for enforcing exclusion, both explicitly through methods like racially restrictive covenants and neighborhood “redlining,” and through many less obvious (and still enforced) economic and legal proxies.

New technologies simply give us new mechanisms to implement these ideas, reducing the cost of enforcement, and obscuring discriminatory intent behind a veneer of modern, tech savvy urbanism.

Encoding injustice, at scale

The same month that the LAPD chased scooter-riding teens through the streets of L.A., I met up in Cambridge with Jascha Franklin-Hodge, former Chief Information Officer of the City of Boston and co-founder of Blue State Digital, the tech strategy firm that helped put Obama in the White House.

In an effort to expand the impact of their work globally, LADOT staff and their private sector partner, Lacuna, a venture funded company run by former Verizon and auto executives, created the Open Mobility Foundation (OMF), a nonprofit organization that Franklin-Hodge now directs.

Over dinner, I explained my concern that by creating new forms of surveillant digital infrastructure in cities we would enable new, unconstrained forms of power to police urban space. Rather than making streets safer, these new technologies would simply reinforce, or even expand existing racial and economic injustice in cities.

I pointed out that at the same time some city leaders are pushing for fine-grained digital regulation of streets, others are grappling with discriminatory, and politically intractable local housing and land use regulations. I argued that there’s a lack of discussion about how exactly “local power” works, who it works for, which kinds of it we want, and which kinds we don’t.

I’d raised this earlier in the day during a talk at Harvard, where folks assembled to hear Franklin-Hodge discuss how real-time collection of citizen-generated movement data, and new digital enforcement methods were transforming urban mobility. He either didn’t understand my question or decided not to address it in public. But at dinner he was less circumspect and remarked how the kinds of premeditated injustice I was describing, exclusionary land use policies like redlining, were problems in city governments in the 1940s and '50s, not today. He said my concerns were an unfair critique of well-meaning city staff working to solve current challenges.

We both left that dinner exasperated.

This language is similar to what I’ve heard in private conversations with city leaders throughout the country. A recent article exploring the MDS controversy quotes another unnamed public official responding to my concerns about the risk of reinforcing structural inequality with new surveillant digital infrastructure:

“We don’t want to be accidentally creating the next redlining,” said one official who could not speak publicly. But, “Do I think dockless [scooters] is the thing that will push this over the line? Probably not.”

According to many who work in this field, these kinds of urban policy decisions, even those specifically designed to change the governance of public space aren’t a part of a larger conversation about unwinding the extraordinary and explicitly discriminatory harm encoded into our cities.

As frustrating these conversations are, they crystalized what has gone wrong with the debate over technology and the future of cities: it has become too focused on the people who see themselves as the builders of “better cities”—questions about their rights, character, and intention—while it lacks consideration for the lives, experiences, and rights of the people whom their work impacts. It also lacks awareness of the history of this work, and how constrained city staff and policymakers are in their ability to navigate questions of racial and economic justice.

Conversations with public officials have also been overly focused on “personal privacy” either as an unattainable goal or as a fungible right that can be traded for something else of value.

A New York Times article from this winter about LADOT's private sector technology partner, Lacuna, and the Open Mobility Foundation claims that giving cities “the ability to monitor their every movement is no longer alarming to users,” because many smartphone apps routinely collect this data. A former city DOT director made a similar argument in 2018, telling me that personal privacy was no longer possible because his “Tesla collects GPS data.” A deputy director of the New York City DOT put it more bluntly last year while explaining why he supported LADOT’s vision for tracking citizens' movement, “privacy is dead.”

Meanwhile, Franklin-Hodge is quoted more recently echoing the same view as the Lacuna co-founder who interrupted me at the LADOT conference: because we don’t explicitly identify users by name in a tracking system privacy isn’t even a concern. “The design of MDS has been, from day one, [protective of privacy]… there is no mechanism within MDS for transmitting personally identifiable information like names, addresses, or even [customer identification numbers].”

It seems the right to privacy in public space is simultaneously dead and fully protected. Perhaps OMF staff and supporters really meant to say that privacy is, in the words of Monty Python, simply “pining for the fjords?”

Regardless, these views fail to recognize the technological and legal risks inherent in collecting citizen-generated data, not to mention the deeper structural harms encoded in surveillance and enforcement systems.

That same Lacuna co-founder, and the chief architect of LADOT’s tracking system, self-published a book and gave TEDx talks exploring how people might one day trade their privacy for financial compensation, like a “zero dollar car” funded via the data it collects. To put it kindly, the economic feasibility of a car paid for by “data” is suspect, but asking users to trade privacy for “free stuff” is already how many technologies work and is one of the most unjust aspects of the current tech economy. In the context of mobility technology should personal privacy in public space really be a “premium feature” available only to those that can afford it?

There are also real risks of expanding injustice via discriminatory policing if we undermine fundamental privacy rights. My hometown police department figured out how to use the exact type of historical, “de-identified” GPS data Franklin-Hodge and Lacuna staff argue is safe, as part of a clever multistep dragnet, called a “geofence warrant,” to identify and surveil anyone that came near a crime scene. We only learned about the practice thanks to an investigative reporter digging through police records.

The New York Times has since reported on the use of this same strategy in other communities and found that it led to the arrest of innocent people—people simply in the wrong place at the wrong time, and whose location data later turned up in a database query, without their names attached. After they’d been deemed “persons of interest” based solely on their travel patterns the court gave the police permission to go collect additional data revealing their full identities.

The Supreme Court has already recognized that location data, and the legal loopholes that allow its collection and use are a fundamental risk to civil liberties. In a 2012 decision in a drug trafficking case involving GPS data collection, United States v. Jones, the court signaled the need to rethink how we govern the use of location data. Justice Sotomayor, after joining the majority, wrote a separate concurring opinion specifically calling out these risks:

...the Government’s unrestrained power to assemble data that reveal private aspects of identity is susceptible to abuse. The net result is that GPS monitoring—by making available at a relatively low cost such a substantial quantum of intimate information about any person whom the Government, in its unfettered discretion, chooses to track—may "alter the relationship between citizen and government in a way that is inimical to democratic society."

The unconstrained use of privately collected GPS data by law enforcement is now part of federal lawsuits. Google CEO, Sundar Pichai, was questioned about the practice in a recent congressional hearing. While legally unable to block the requests, Pichai noted that the company has gone to great lengths to raise awareness over the increasing number of GPS data requests it receieves from law enforcement.

Despite growing concern over GPS data undermining rights of citizens and possible action by the Supreme Court, cities are pressing on and arguing these constitutional limits do not apply to emerging forms of digital traffic enforcement.

But this debate is about more than what the courts allow. The willful dismantling of digital privacy in public space is a symptom of a greater failure, not only of law and technology, but of our ability to imagine a more just future.

Deploying these kinds of technologies in urban governance demonstrates a lack of empathy towards people’s experience of public space and the ways existing forms of surveillance exacerbate structural inequality. Comparing the privacy risks of Tesla ownership with the kind of discriminatory and surveillant infrastructure we routinely use to govern and police streets indicates a profound lack of understanding of what’s actually being debated.

Worse, this debate frames “privacy” as a false choice between public goals and individual rights, things that are not in tension, but are actually mutually supporting.

Many of my conversations with city officials focus on loss of privacy as a necessary compromise as public agencies attempt to regulate and rein in new forms of private power embedded in digital platforms like Google, Uber, and Amazon. The argument goes, if a company has the ability to track its customers, why should a city be constrained in its ability to track its citizens in pursuit of a form of countervailing “public” power? Putting aside the substantial difference that, unlike local government, Google does not have the power to arrest its customers this is a misguided and dangerous path to corporate oversight, and one that does not serve the interests of citizens.

In the Harvard Law Review article What Privacy is For professor Julie Cohen questions this line of thinking and explores the corrosive impact of normalizing surveillance in both public and private forms. As Cohen writes, surveillance of any kind enables a “modulated society” at odds with democratic values, not only because it expands police power but because it undermines a more fundamental right to self-determination, and amplifies existing power asymmetries:

Privacy shelters dynamic, emergent subjectivity from the efforts of commercial and government actors to render individuals and communities fixed, transparent, and predictable. It protects the situated practices of boundary management through which the capacity for self-determination develops.

…

The embedding of surveillance functionality within market and political institutions produces “surveillant assemblage[s],” in which information flows in circuits that serve the interests of powerful entities, both private and public.

In the modulated society, surveillance is not heavy-handed; it is ordinary, and its ordinariness lends it extraordinary power. The surveillant assemblages of informational capitalism do not have as their purpose or effect the “normalized soul training” of the Orwellian nightmare. They beckon with seductive appeal. Individual citizen-consumers willingly and actively participate in processes of modulation, seeking the benefits that increased personalization can bring. For favored consumers, these benefits may include price discounts, enhanced products and services, more convenient access to resources, and heightened social status. Within surveillant assemblages, patterns of information flow are accompanied by discourses about why the patterns are natural and beneficial, and those discourses foster widespread internalization of the new norms of information flow.

…

By these increasingly ordinary processes, both public and private regimes of surveillance and modulation diminish the capacity for democratic self-government.

In my conversation with city officials around the country I've raised a point similar to Cohen’s and asked if, rather than duplicating problematic technologies, the city had a responsibility to push back against private sector surveillance by expanding privacy protections on behalf of citizens?

At the state and national level, progressive and conservative reformers alike are re-thinking how we regulate tech platforms, and expanding privacy protections are a key element of that effort to rebalance economic and political power. Yet in New York, the DOT deputy director found my argument that the city should champion the rights of its citizens rather than track them naively optimistic and responded, “We won’t win that fight.”

This position is not only deeply cynical, it also undercuts the argument made by many city transportation officials that the underlying goal of “public” surveillance infrastructure is actually a check on corporate power. The kind of local policy we see emerging in the US looks less like corporate oversight and more like envy.

Intent aside, the transport policy community finds themselves apart from the growing tech reform movement as cities promote the expansion of problematic technologies rather than directly addressing and mitigating potential harms. This indicates a lack of coherence in how transport policymakers respond to the type of power embedded in private digital platforms. These platforms are not powerful because they surveil citizens' movements, they’re powerful because they fundamentally restructure markets for public services and they use unregulated digital surveillance as a tool for expanding that market power.

More successful regulators combatting new platform-mediated mobility and logistics companies have focused directly on these market dynamics, reinstituting fundamental labor protections alongside competition and consumer pricing regulations. These kinds of regulations are aligned with the broader tech reform movement and are an existential threat not only to mobility services firms like Uber, but retail and logistics behemoths like Amazon. Yet despite their power this type of regulation does not depend on collecting the kind of invasive citizen-generated data proposed by LADOT and OMF.

The beneficiaries of more fundamental reforms that focus on market power aren’t wealthy homeowners looking to exclude outsiders from their neighborhoods. This kind of reform most directly benefits the low-income (often BIPOC) workers that power these platforms, and price-sensitive consumers using the services as a lifeline. In other words, beneficiaries of meaningful corporate reform and accountability are precisely the same people being policed by LADOT and OMF's approach to regulation.

Local power vs Local minima

Rather than using technology to re-imagining the governance of public space in pursuit of things like safety, equitable access, fair employment, and transparent and affordable mobility services, LADOT and OMF argue that new technologies justify new forms of surveillance and control. Perhaps unsurprisingly LADOT and OMF’s work is now at the center of an ACLU lawsuit arguing that the technology violates citizens’ Fourth Amendment rights, as well as California laws limiting digital surveillance.

In February, the California State Senate called a joint Transportation and Judiciary committee hearing to ask why LADOT’s regulation of public streets depended on tracking citizen movement. In urban policy circles, state preemption is (rightly) talked about as one of the most powerful forces undermining progressive reform. This is particularly true in transportation, where there’s a long history of state governments, often representing majority suburban and exurban populations, forcing car-oriented highway policies on urban communities. The city officials arrived in Sacramento prepared to defend their sovereignty.

But what unfolded did not look like an uncaring state legislature stomping on the progressive dreams of cities. City officials representing both their own communities and the Open Mobility Foundation argued against any limits on their ability to track and store data on citizen movement. Despite being asked repeatedly what regulatory purpose such expansive and unrestrained collection might serve, they could not provide clear examples of how the data would be used, or what laws’ enforcement might necessitate amassing such granular and sensitive information.

Other speakers at the hearing, including one of the ACLU litigators now suing LADOT, offered constructive solutions. They pointed out that many of the obvious policy goals, like regulation of commercial fleets, improved parking enforcement, or mapping how we use streets for infrastructure planning are possible and actually more easily accomplished without collecting and storing data that put citizens at risk. Yet, city officials argued against any limits on the grounds that restrictions now might undermine future, still unknown, regulatory or enforcement needs.

In an at times heated exchange, the chair of the judiciary committee reminded city staff that under the state constitution the work of public officials is subordinate to the rights of citizens. The chair of the transportation committee scolded one city official from the district the senator represented for not engaging in good faith debate over limits on collection of citizen-generated data.

In a moment of legal showmanship, city officials presented the committee with a memo during the hearing, arguing that the legislature misunderstood its own laws on digital privacy—laws specifically designed to prevent over-collection and misuse of personal data by government agencies. Because no one on the committee had been given time to read the memo it became clear that a substantive discussion of legal merit was now impossible. (I had to make a Legislative Open Records Act request to get a copy of the memo as the surprise presentation prevented it from being properly entered into the hearing’s public records. The memo did not make a compelling argument. The crux of the cities’ position was that transport regulation and traffic laws enacted by DOTs are different from other forms of policing and should not be subject to the same legal constraints. It also made claims about limits in MDS data collection that are patently false.)

In the absence of constitutional limits, or even an ethics framework that provides guardrails against abuse, we are asked to defer to the character and the intentions of the people implementing these programs as our defense against injustice. As Franklin-Hodge argued, these are good people attempting to build a better city.

This misunderstands how cities are built, and who builds them.

So many who work in urban policy wear finishing Robert Caro’s The Power Broker as a badge of honor, a book about modernist icon and unabashed segregationist, Robert Moses’ career re-designing New York City in his image via the wrecking ball of “urban renewal.” At the same time, so few talk about reading Isabel Wilkerson’s The Warmth of Other Suns, a biography of southern Black families caught up in the Great Migration as they moved to, and transformed urban centers across the country. These books are almost equally long, both by Pulitzer-winning authors. But the lives documented in the latter have more to say about the building of the American city, perhaps even New York City specifically, than anything ever written by or about self-proclaimed city-builders like Robert Moses. In fact much of Moses’ work was a simply a reaction to (and against) the cultural and demographic shifts documented by Wilkerson—the same shifts LAPD officers were reacting to as they terrorized Watts residents, and chased down “lowriders.”

But the kind of power Caro writes about is titillating even as we, as white urbanists, critique it and talk about how today's generation of policymakers are better than that. As a profession, I suspect the urban policy community finds discussion of "city power" and powerful urbanists attractive because deep down they believe that our cities are things they make, rather than an embodiment of our culture.

Unfortunately, structural inequality and systemic racism are not the product of our intentions, they are the consequence of our actions. As the former mayor of Minneapolis, Betsy Hodges, wrote in a recent New York Times Op-ed:

White liberals, despite believing we are saying and doing the right things, have resisted the systemic changes our cities have needed for decades. We have mostly settled for illusions of change, like testing pilot programs and funding volunteer opportunities.

These efforts make us feel better about racism, but fundamentally change little for the communities of color whose disadvantages often come from the hoarding of advantage by mostly white neighborhoods.

In Minneapolis, the white liberals I represented as a Council member and mayor were very supportive of summer jobs programs that benefited young people of color. I also saw them fight every proposal to fundamentally change how we provide education to those same young people. They applauded restoring funding for the rental assistance hotline. They also signed petitions and brought lawsuits against sweeping reform to zoning laws that would promote housing affordability and integration.

We can see this reality at work in the collision of Los Angeles’ homelessness crisis and LADOT’s authority to regulate parking. Multiple times in recent years the L.A. city council asked LADOT to create parking regulations that prevent citizens from sleeping in cars. These laws are unconstitutional, not to mention an immoral criminalization of homelessness. They have been repeatedly struck down in federal court, and each time one law is overturned a new law is drafted by the city council, and each time LADOT is forced to implement it.

I have no doubt that many LADOT staff find these laws reprehensible, yet they also hold the power to draft regulations that allow police to roust the city’s most vulnerable population from sleep, and search and impound their cars. Their city council can force them to wield this power in ways that re-entrench existing structural inequality, without consideration of constitutionality or morality.

During the 2019 debate over a similar law enacted in Berkeley, CA, the mayor explained how “quality of life” concerns, and the almighty quest for "parking availability" justify these laws:

“While we are doing everything we can to help those people who are without homes, we have to establish reasonable policies and limits on how many more RVs can come to our city to ensure that parking is available, and to ensure that our businesses and residents can enjoy a decent quality of life as well.”

In L.A.'s case, LADOT staff worked with the police department to make maps showing streets where sleeping is allowed and where it is prohibited. These laws are nothing more than a new flavor of redlining. And they are not different from laws created in most US cities in the 1940s and '50s prohibiting the construction of low-cost alley dwellings.

A similar restriction was written into the deed of my home in 1946, followed by the requirement that “no person of any race other than the Caucasian race shall use or occupy any building.” The adjacency of these two clauses is not a coincidence.

Just a year after my deed was drafted the Supreme Court blocked the enforcement of explicit racially discriminatory covenants on the grounds they violate the Equal Protection Clause of the constitution. Yet, by design, the actual words cannot be removed from the deed without petitioning every landowner in my neighborhood. And despite the ruling against explicit racial discrimination, the adjacent clauses limiting development rights, and preventing construction of smaller, lower-cost homes are still in effect and are now actively enforced as part of city-wide zoning rules.

Not only am I blocked by my deed from building low cost housing, it is now the job of city employees to uphold these development regulations, explicitly designed to exclude low-income and BIPOC members of the community.

In Los Angeles, LADOT’s new motorized version of discriminatory housing policy simply expands the scope of enforcement of these types of rules, leveraging the city’s parking regulations in an attempt to outlaw homelessness.

Privacy in public

In striking down an earlier LADOT regulation against sleeping in cars, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals cited the 1972 Supreme Court decision Papachristou v. City of Jacksonville which overturned a similar regulation outlawing “vagrancy” and people using public space “without any lawful purpose.”

Justice Douglas’ eloquent majority opinion in Papachristou cited the vagueness of the law, and the invasive, and inherently discriminatory forms of policing required to understand why someone was on the street:

Persons “wandering or strolling” from place to place have been extolled by Walt Whitman and Vachel Lindsay. The qualification “without any lawful purpose or object” may be a trap for innocent acts. Persons “neglecting all lawful business and habitually spending their time by frequenting … places where alcoholic beverages are sold or served” would literally embrace many members of golf clubs and city clubs.

Walkers and strollers and wanderers may be going to or coming from a burglary. Loafers or loiterers may be “casing” a place for a holdup. … The difficulty is that these activities are historically part of the amenities of life as we have known them.

They are not mentioned in the Constitution or in the Bill of Rights. These unwritten amenities have been in part responsible for giving our people the feeling of independence and self-confidence, the feeling of creativity. These amenities have dignified the right of dissent and have honored the right to be nonconformists and the right to defy submissiveness. They have encouraged lives of high spirits rather than hushed, suffocating silence.

…

Those generally implicated by the imprecise terms of the ordinance - poor people, nonconformists, dissenters, idlers - may be required to comport themselves according to the lifestyle deemed appropriate by the Jacksonville police and the courts. Where, as here, there are no standards governing the exercise of the discretion granted by the ordinance, the scheme permits and encourages an arbitrary and discriminatory enforcement of the law. It furnishes a convenient tool for “harsh and discriminatory enforcement by local prosecuting officials, against particular groups deemed to merit their displeasure.” … It results in a regime in which the poor and the unpopular are permitted to “stand on a public sidewalk … only at the whim of any police officer.”

Douglas’ opinion reads like an urbanist manifesto on the social value of privacy in public space—the right to be let alone on the street.

But what’s also striking is how easily it could be read today as an indictment against the men who murdered Ahmaud Abery, a Black man on a jog in a Georgia town in February. Or the murder and brutalization by police of so many other Black and Brown people attempting to enjoy public space in America, only to be confronted with the violent reality that these “unwritten amenities” are not theirs to enjoy. The freedoms Papachristou describes, movement free of surveillance, accusation, and harm are only available to some of us.

As Seo writes in Policing the Open Road, Douglas’ opinion references a law review article, Police Questioning of Law Abiding Citizens, written a few years earlier by Yale professor Charles Reich, drawing substantially from his own experience as a then-closeted gay man frustrated by frequent and completely arbitrary stops by police:

On one occasion when a patrol car flagged me down for a “routine check” on Route 2 near Boston, the officer, after ascertaining my name by looking at my driver’s license, said “What were you doing in Boston, Charlie?”

Reich made a compelling argument for the “need for privacy in public,” and the harm a lack of privacy brings to persecuted groups of people. His legal scholarship shaped a number of critical court decisions expanding due process protections not only for drivers and walkers but public benefits recipients and other vulnerable groups interacting with administrative processes.

One of the more common arguments made in favor of surveillant systems is that public agencies already collect other sensitive information, and that these existing privacy compromises justify, or at least excuse, new forms of surveillance. Franklin-Hodge made exactly this argument in favor of cities collecting citizen-generated movement data, “I’m a former city CIO. I got a look at all of the types of data that cities stored and collected. We worked with a lot of data that’s a hell of a lot more sensitive. We’re sitting on ambulance data, student records, sensitive financial data from applicants for public housing.”

But rejection of this type of administrative whataboutism was at the heart of Reich’s work expanding due process rights for both public benefits recipients and users of public space. Just because someone needs public housing doesn’t mean the decision should be at the whim of a discriminatory, or a vague and ever changing review process, or subject them to new and unnecessary forms of surveillance and intrusion. He argued the same is true for streets, people should have the right to public life free from surveillance or discretionary and unjust forms of policing.

As Seo notes, Reich’s work also called into question how we define policing in the name of public safety. Echoing Weismantel’s proposal for limiting undesirable “through traffic” on St. Louis streets with better roadway design, Reich wrote, “highway safety is more a function of better engineering of cars and roads, and better training of those who drive.” He recognized that, “in one way or another, the police were policing difference, and that provided safety.” Policing of streets was never truly about safety in any fundamental sense, but rather conformity.

Yet despite his personal understanding of persecution, Seo notes Reich’s writing failed to document the full scope of racial injustice embedded in the policing of public space. Even though it was written just a year after the Watts Uprising his concern with policing was not violence, something he never documented experiencing as a white Yale law professor. Instead he focused on things like “tone”—being called “Charlie” by a police officer as an intentional form of disrespect. The very title of the article Police Questioning, not Police Brutality or Police Violence against Law Abiding Citizens indicated a lack of understanding of the depth of injustice and harm faced by Black and Brown people in their encounters with the police.

While Papachristou expanded due process rights for motorists and pedestrians, and clawed back the use of vague transgressions like “prowling by auto” as a justification for a traffic stop, it did not address the related question of equal protection. Perhaps in part because both Douglas and Reich failed to directly address racial inequality in policing, the Papachristou decision only returned the constitutional right to due process to some of us. White people, and white car owners in particular, now expect the kind of “privacy in public” Reich fought for, yet a half century later those rights are still far from universal.

Regarding their narrow focus on due process as a procedural issue, over a substantive expansion of rights, Seo writes, “Douglas and Reich’s capitulation reflected a larger development underlying constitutional criminal procedure: the transition to police law enforcement as a mode of governing for the public welfare.”

Today many white urbanists call to expand the ways our cities police public space in the name of things like bike and pedestrian safety. We want streets to work better, and be safer (for some) by deploying new laws and new forms of enforcement without recognizing that we’re only compounding existing, unresolved injustice. We’ve successfully reclaimed streets for ourselves at the same time we’re unable to see the pervasive forms of violence and discrimination we’ve tacitly accepted and normalized.

Because of this we fail to recognize the discriminatory animus of parking regulations that ban homelessness, or “no through traffic” restrictions enacted in the 1990s as part of the “war on drugs.” And we fail to see chasing teenagers with helicopters as a violent and disproportionate act. Or how the creation of tracking and enforcement systems that violate fundamental rights in the name of “public safety” is a symptom of a deeper societal failure. And it explains how our DOT directors have become confused about the difference between their Tesla’s navigation system and police surveillance.

Digitizing justice

These laws policing public space, and the new forms of digital enforcement that support them, are only attempts to return us to a time before Papachristou. They help define new transgressions that enable new, constitutionally allowable forms of discriminatory policing.

The complexity and dynamism of digitally encoded enforcement hides the details of these rules and further shields them from constitutional scrutiny. Unless explicitly designed otherwise, digitally-mediated enforcement is both more opaque and more manipulatable, and will absolutely expand already pervasive forms of discrimination and inequity in the governance of public space. The new “digital truth” now preventing outsiders from traveling through Sherman Oaks should serve as a warning of what’s to come.

Putting aside the most obvious reason for the persistence of efforts like these to divide our cities—systemic racism masked by arguments for “traffic safety” or “orderly streets”—why don’t more of us, as white urbanists, see through and fight back against these thinly veiled uses of police power to evict people we fear or dislike from the neighborhoods and streets we claim as our own?

I suspect the lack of visibility and public debate is an indication of how successful our more openly racist city-building forefathers were in their plan to create a segregated society. We’re now complicit in the plan’s implementation in part because it has become so pervasive that it is hard for those of us benefiting from it to even see its presence.

Perhaps the people pushing back against claims of “intentionality” really mean to say that the process unfolding today is either invisible to them or, more likely, that it is simply inevitable. To reframe Franklin-Hodge’s defense of the people caught up implementing this plan, can injustice that everyone expects to happen actually be called premeditated?

The mechanics of how we implement these laws via transport policy also hides the ugliness of enforcement from view in a way that obscures contemporary forms of discrimination. Unlike a public zoning board meeting where we at least hear coded language about “changing neighborhood character,” there’s little formal public record of the injustice and trauma inflicted by a discriminatory traffic stop in all but the most horrific cases. There’s even less record of a trip not taken out of fear, or because some digital enforcement system or algorithmic routing tweak prevented it from even occurring.

In a statement made at recent city council meeting in Durham, NC, Mayor Pro Tempore Jillian Johnson described her experience of surveillance and policing of public space as a Black woman and mother, and how new forms of documentation are forcing those of us unfamiliar with this reality to see the violence embedded in the ways we govern streets:

As a mother of two Black boys, my family and I face the consequences of this epidemic every day. A few months ago I sent my 13 year old son to a neighbor’s home to give them a misdelivered package, and I waited on my front porch the whole time he was gone to make sure he came home. I regularly see posts from neighbors on listservs reporting the presence of black people in their neighborhoods as if we don’t have the right to exist. As a child in the 1980’s, my mother warned my little brother not to play with toy guns so the police wouldn’t think he had a real gun and shoot him. Decades later, the only thing that has really changed is that the ubiquity of phone cameras and live streaming technology has brought the reality of this epidemic to a new and broader audience.

(Johnson is one of the most progressive and impactful city leaders we have today. I encourage you to read her full statement about how we police our cities and what must change.)

As Princeton professor Ruha Benjamin writes in her book Race After Technology, emerging forms of digital policing are fundamentally incompatible with constitutional presumption of innocence and warrant protections, yet these practices are “consistent with the long history of racial surveillance endured by Black people.”

The progressive possibility of digital enforcement isn’t to expand the coverage and efficiency of policing but rather to narrow the scope of what is enforced, and ensure the design of those enforcement systems prevents abuse. Instead of “policing difference” in the name of safety we should only deploy technology that enforces, and measures progress towards a more inclusive form of urbanism that is truly safer for all.

As Reich, Weismantel, and a generation of planners, engineers, and advocates have shown us, we know how to build safer streets and cities, and none of it requires policing or new forms of surveillance. At the same time we must recognize, as Reich documented in his work on justice for public benefits recipients, that policing is about more than uniforms and guns. Reform must begin with the laws themselves, and a recognition of the many ways we "police" streets. It also requires confronting the economically regressive roots of traffic enforcement based on fees and fines, and the resulting criminalization of poverty—immoral in and of itself, but also a tool deployed as a proxy for illegal forms of explicit racial discrimination. Many cities rely on these fines a critical source of revenue, and there's evidence of increased fiscal dependence on fines as cities face dramatic revenue shortfalls due to COVID.

Only with a more fundamental foundation of justice in place, thoughtfully designed tools for managing traffic can be supported by new technologies. Some of these tools might support narrowly defined enforcement goals. With intentional effort and extreme transparency new systems can be designed in ways that make enforcement less vulnerable to discriminatory politics and manipulation. For example, universally enforced speed limits, governed by ubiquitous speed cameras that collect only the data required to issue tickets can make streets safer without tracking anyone. But we choose not to do this because those with political power prefer traffic laws that are deployed discretionarily. In many cities the placement of traffic cameras is a matter of political power. In this way traffic law becomes a tool in policing difference, not safety.

Unfortunately, this kind of clear, upfront definition of public purpose and accountability is the exact kind of restraint that LADOT and other OMF member cities argued against in the California Senate, saying this should instead be a matter of local control.

But how do we expect a just outcome in communities that already openly surveil and question the legitimacy of their BIPOC residents via neighborhood listservs? Situations like this are why constitutional constraints exist, and why as a professional community transport and urban policymakers have a responsibility to precisely define public goals, and limits, and new forms of transparency and accountability needed in their implementation.

Building digital infrastructure that does not perpetuate or expand injustice, just like cities themselves, takes profound and explicit effort. We are not off to a good start.